“What we have learned from our teachers is far more important than their physical presence. Our teachers have transmitted to us the fruit of all their wisdom and experience.”

Thich Nhat Hanh

Thousands of athletes have had the opportunity to be coached by Gordon Gillespie. Arguably the most outstanding coach that the country has ever seen, Gordie amassed records virtually unmatched when viewed through the filters of victories, team sports, and longevity. He coached baseball, football, and basketball on the college, high school, and pre-high school levels over a 59-year period while earning multiple awards and recognitions.

There are also hundreds of men who have had the chance to assist head Coach Gillespie during those 59 years. They may have been acting as volunteers, part-time staff, or full-time employees who were dedicated to a particular sport while being committed to the revered leadership of Gordie.

And then, there are a few of us who have actually played for Gordie and also have had the privilege of being his assistant. I consider myself as one of the most fortunate men who have played two sports for four seasons and then became his assistant for five years. Those experiences would influence me in ways that were nearly comparable to the roles that my parents played.

As athletes, my teammates and I viewed Gordie as Zeus recently arrived from Olympus. We held Coach in the highest regard as a second father, mentor, and leader. We didn’t question, talk back, or argue because we respected him and his decisions. Our respect for him was only exceeded by his respect for us. We knew how much that he valued and loved each one of us.

As an Assistant Coach

I knew that players (like me) had also feared the Coach. But my fear mostly was about not disappointing him. As I assisted him, I now saw Gordie as genuinely caring man who knew that his players were young people who made the mistakes that young people make. He knew that some guys smoked, drank, and broke rules. He was fully aware that it was his duty to be a disciplinarian, but down deep he understood them and supported them.

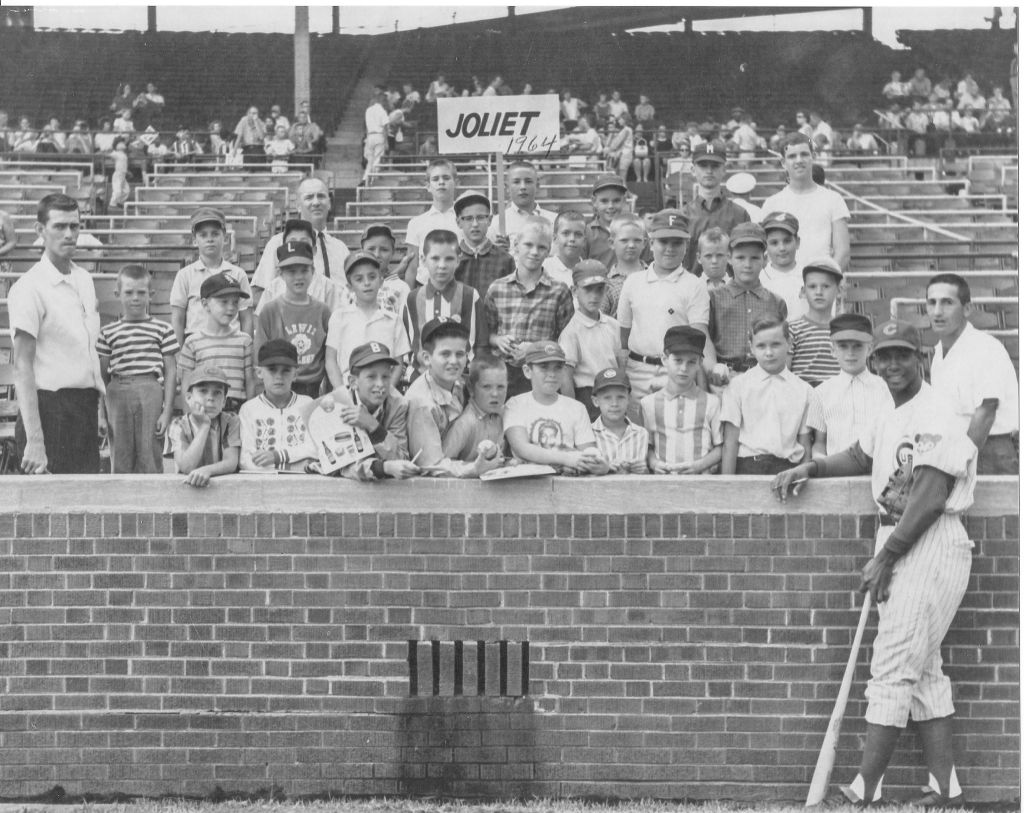

Although I now saw him as less mythical, Gordie Gillespie retained his title as a most magnificent human being. He could be “old school” one minute and “new school” the next. He could coach 6-year kids as well as college seniors in football, baseball, basketball. As his baseball assistant coach, I enjoyed five years under his tutelage at Lewis College and one summer in the Ernie Banks Baseball School.

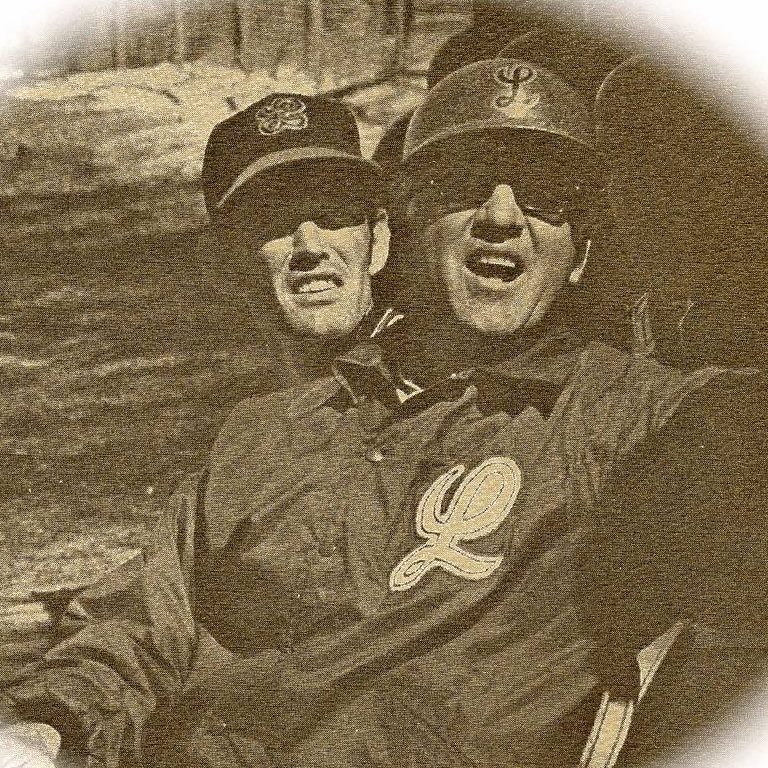

A college baseball schedule can be far more travel extensive than many other sports. For Lewis College between 1968 and 1972, conference games usually consisted of same-day trips plus a few overnighters. Before the conference schedule, Lewis would routinely schedule a trip to warmer weather.

Being located in the north where weather conditions precluded many March games, Lewis began implementing a spring southern trip schedule for a two-week period. During that time, the schedule might include 16 games (including double headers) in 14 days. Game times actually consumed relatively few hours of our days.

The rest of the time was spent in the bus, at meals, in a motel room, or at a movie with Gordie. We would talk baseball: analyzing team personnel, game strategies, psychology, and opponents. After baseball talk, the most interesting time was talk about families, former players, and the future. Gordie loved talking about the old days of baseball. He never spoke about himself except about his own perceived weaknesses and failures.

Prior to the spring trip, practices began indoors about the first of February. Practices were meticulously prepared and organized. How could we capitalize on every minute in the limited indoor facilities? We sought innovative methods to build skills and create game-like situations using wooden pitching mounds, string strike zones, and sock balls. Baserunning was coordinated with pitching drills.

On the field, concurrent and coordinated drills by fielding position were coupled with walking leads. No one on the field was standing still. Pre-game infield and outfield practice was meant to get everybody active and productive. With execution and precision, each pre-game action dazzled observant baseball scouts.

Looking back, I can still hear his exaggerated, dramatic demonstrations of faked anger at his athletes’ failure to execute a drill. Watched how Coach could inspire, encourage, and console; reprimand with tact; read the situation and anticipate the next 5 moves. If only these qualities could be bottled, the genie would have been replaced.

During the off-season, we spent countless hours working on the field, giving coaches’ clinics, and negotiating with upper administration. Gordie’s special concern for each student athlete, regardless of the institution’s policies, sometimes set him at odds with the bureaucracy. Meanwhile, the bureaucrats seemed intimidated by the Gillespie aura and usually yielded to his requests.

As much as wanted to coach because of Gordie, I finally realized that it was because of him that I decided not to make a career of coaching. In order to be an excellent coach like him, I would need coaching talents not in my tool box. I saw Coach’s focus, drive, and dedication to baseball as major league quality whereas I was destined for the minors.

My conclusion was that I was better suited to seek other higher education venues in order to help students find their respective paths. But there was no question that the Lewis coaching and intramural experience had formed a sound foundation of leadership, organizational, and people skills that would be required for any future undertakings.