“The dash between dates holds the essence and spirit of the deceased. It doesn’t take long for memories to fade. Precisely why every family needs a historian to capture and relate stories of each member.”

Sharon Mosier, Educator

I am swimming in genealogic facts: birth and death dates, names of relatives, and locations. They come from a variety of sources: The History of Will County, notes and letters from old relatives, and Irish, Dutch, and German sources. As I sit at my desk, binders, file cabinets, and “cloud” files virtually plead for rational compilation and organization.

Having accumulated these puzzle pieces for over 30 years, I periodically consult them for stories. My dream is to redirect those pieces, reconcile some inaccuracies, and convert them into illuminative narratives that can be readily accessed, understood, and appreciated by future generations. Facts and data tend to be meaningless without a narrative.

And so, my story of the first “Kennedy” to reach the shores of America.

Jim’s Own Words? An Imaginary Journal Entry

September 12, 1854.

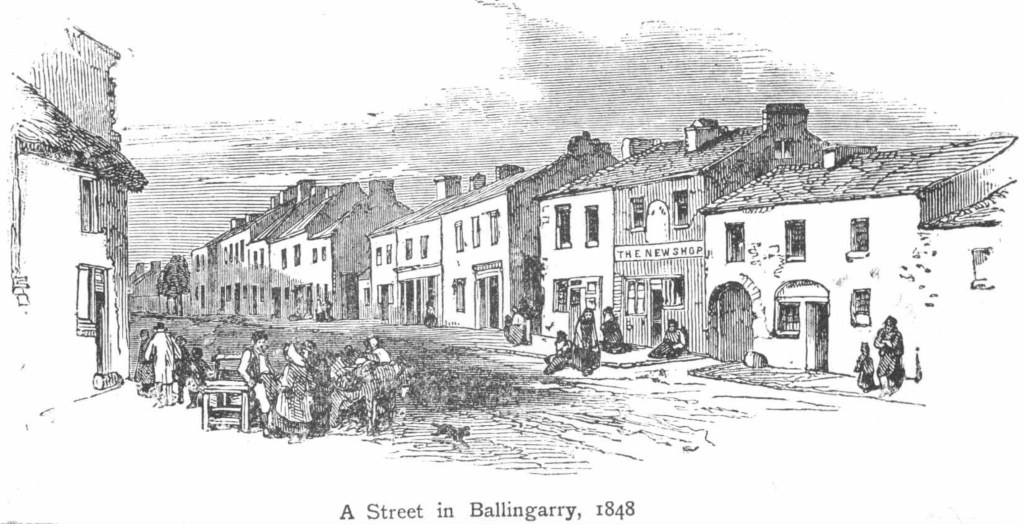

“I am 17 today and live in Ballingarry, County Tipperary, Ireland. My father is John Kennedy, and my mother is Catherine. I have two brothers – Tom (older) and John (younger) – and a sister, Margaret. She is the youngest. We live on a small plot of land, and raise potatoes and cabbages, but the potato crop has been horrible for the past 8 years. Thank God that dad was able to get a little work at the coal mine.

We are lucky to be able to have food on the table most days, so we go to the soup kitchens sometimes. Other times we run out of food, forcing my brothers and me to go to the workhouse in Cashel. Breaking stones is hard work for kids and the Indian meal they give us doesn’t taste good. They called it “stirabout.”

Saw three more burials yesterday. The folks digging the graves also look like they are about to die of starvation and sickness. Dying burying the dead.

I have made up my mind to leave Ballingarry and go to America if I can find enough money. I hope that the rest of my family can also leave as soon as possible, please God.“

Historical Facts

Between 1845 and 1852, over 1 million people died from starvation and disease and another 2 million emigrated from Ireland. Property was primarily owned by British absentee landlords but worked by sharecroppers. Families were evicted and the free-market doctrine of “laissez-faire” promoted the decimation of the population. Survival had depended on potato crops, but blight (a fungus that destroyed the leaves and roots) had all but eliminated that primary foodstuff.

British sentiment was that the Irish were at least one level below being human. They would easily take public monies and food while refusing to work. The only recourse for the starving population was in the form of public works (workhouses) and soup kitchens. In Ballingarry with a population of 7,062, a total of 5,678 were receiving food in soup kitchens in August of 1847.

As this calamity was happening, large quantities of food were being exported to Great Britain during the blight. In Livestock, butter, peas, beans, rabbits, fish, and honey were exported while millions of Irish were starving.

The “Battle at Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch”

It was only a matter of time that the Irish would rebel against the British control over the poverty-stricken people. In 1848, Ballingarry would become the first site in a series of rebellious flareups that would end in open conflict.

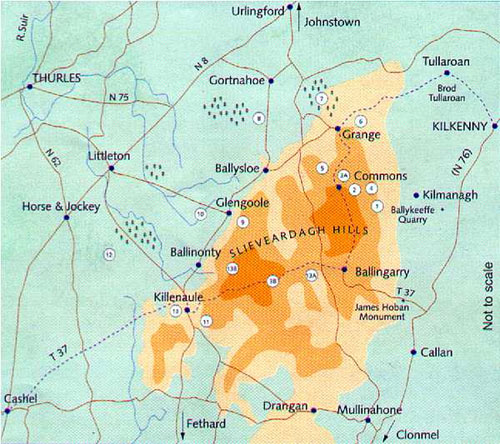

A group called Young Irelanders – inspired by Daniel O’Connell, the leader of the Irish Independence movement – marched toward Ballingarry coal mine regions of Slieveardagh and confronted a police force. Outnumbered, the police took refuge in Widow McCormack’s house.

Armed with rocks and sticks, the rebels battled the enclosed police, but it was no match for police guns. Two “Irelanders” were killed, and the remainder scattered. It marked the first clash of the Irish rebellion.

The Decision to Leave

Within a short distance from the battle, the John Kennedy family took note of the helplessness facing future generations and considered their limited options. This was the only place that they knew, a place where their ancestors had lived for generations.

The Battle in their backyard shook them to the core but it would take six more years of witnessing the deaths of neighbors and relatives to convince John and Catherine that the welfare of the family depended on leaving Ireland. Many other local families had come to the same conclusion and were now gone.

Whether Jimmy volunteered or was drafted by the family is unknown. He wasn’t the oldest son, but perhaps he was more adventurous. Now 17 years of age, he would become the first of the family to venture to America. If things worked out, maybe the rest of the family could follow his trail.

Jim Kennedy Arrives in America

The following letters that James Kennedy might have written to his parents, John and Catherine Corcoran Kennedy, after his arrival:

May 15, 1855.

“Dear Da, I hope all is well with you and mum. I have just arrived in New York and have seen a notice that jobs are available on the docks in New Orleans, wherever that is. I think I will go there and make some money. New York City is a large city with people from Ireland and many other countries. It’s not very clean here but far better than what we had in Ballingarry.

When I think of it, we were luckier than many of our friends and relatives. Our potato crop was bad because of the blight, but you were able to still work a little in the coal mine, thank God. I knew of some of my friends still work in the workhouse breaking rocks for a little money. Other friends died not only from starving but also from sickness. Many others had just enough money to leave Ireland.

During the long boat ride here, I thought a lot about that fight at widow McCormack’s house. I would have joined the Young Irelanders, but I was too young, being 11 at the time. Brother Tom couldn’t either because he was only 12. I learned on the boat that some people refer to it as the Battle of Widow McCormack’s cabbage patch.

Too bad that the “Young Irelanders” were outmanned and didn’t have the weapons that the police had. At least they might have started a movement for Irish independence someday that Dan O’Connell talks about. Sadly, I also heard that the Young Irelanders’ leaders, O’Brien and McManus, were caught and sent to an island near Australia.

I hope that you and mum consider coming to America as soon as possible. You know about other Irishmen who came over here and are now living near a small town in a state called Illinois. They say that we could get farmland there for $1.25 per acre.

For now, I am on my way to work on the docks in New Orleans. I will try to rejoin the family when you come to America.

I will be sending money as soon as I start working. You mentioned that the landlord may be helping pay for our family to leave Ireland? I guess that landlords save money by sending their tenants away. They want to get land back to raise cattle and pigs rather than crops.

Your faithful son, Jimmy.”

Three Years Later

January 17, 1858

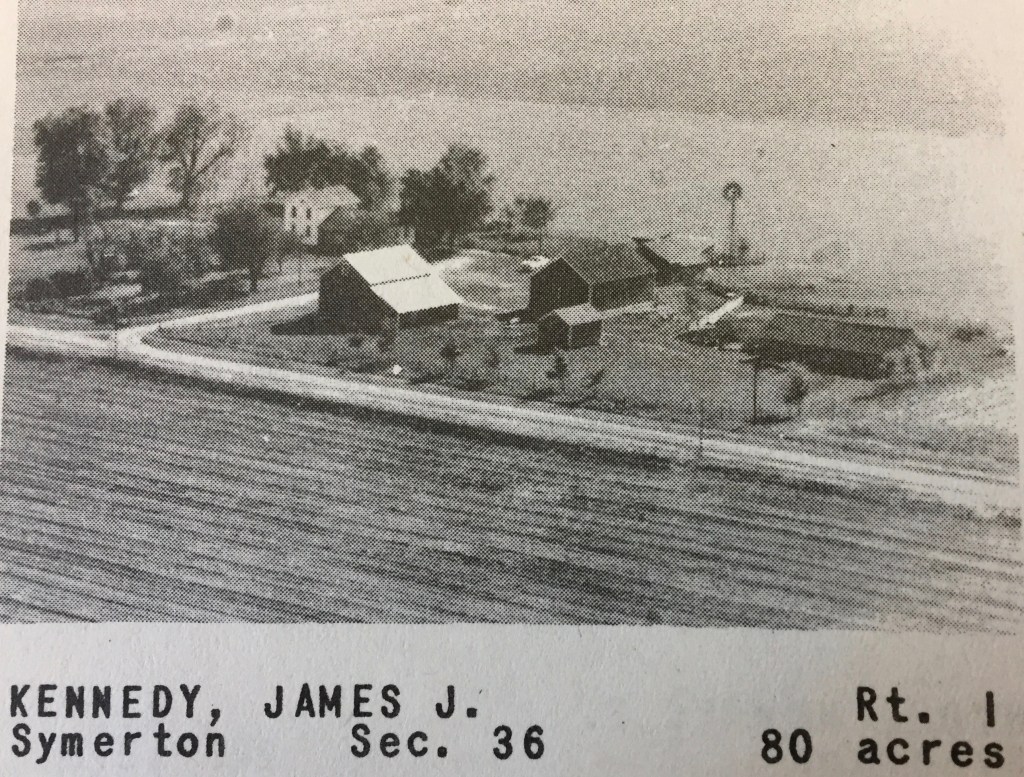

“Da, I plan on leaving New Orleans soon and will be joining the family at your farm in Illinois. You mentioned that you bought 80 acres of land in a place called Florence Township (section 25, whatever that means) near the town of Wilmington. Compared to our land in Tipperary, that is a huge amount of property. When I arrive in Illinois, maybe we can increase it by another 80?

But maybe that’s a pipedream.

Work on the docks has been good and I have saved a lot of money. My fellow workers are an interesting group of folks. This has been the first time I have ever seen African people. Many are slaves of rich owners, and some are not slaves and making money that they can keep. They do make less than I do but work just as hard. It doesn’t seem fair to me, but that is the system here in New Orleans. I thought that we Irish were abused by the British, but slaves are being beaten for the slightest mistake.

Now that you have a farm of your own, I look forward to being a farmer again and raising livestock. Horses have always been of interest to you so I expect that we will raise them also.

I hope that you haven’t forgotten me. I have missed seeing you, mum, my brothers (John and Tom), and sister Margaret. After I get established in Florence, maybe I will meet and marry someone local there.

See you in April.

Love, Jimmy“

The Rest of the Story: Jim Kennedy in Illinois

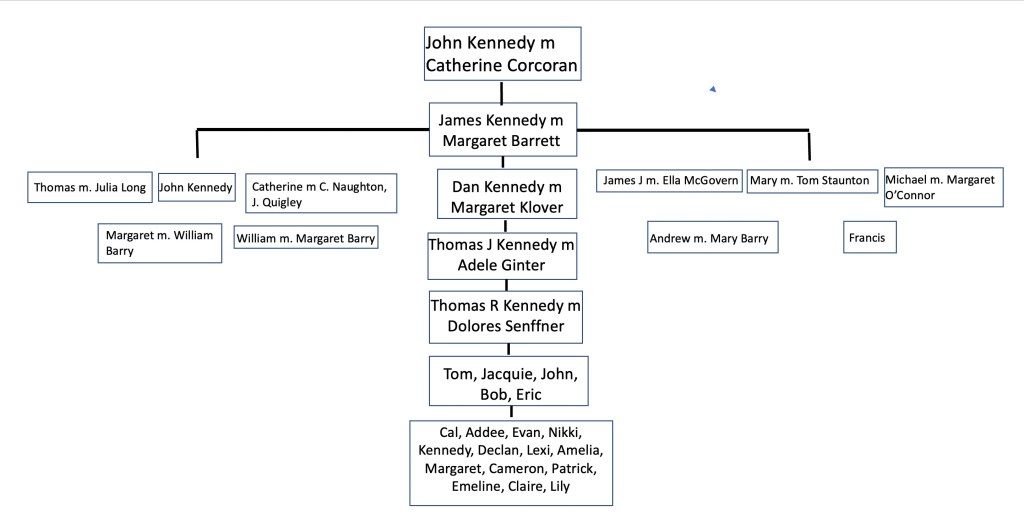

Jim did rejoin his family in Florence Township in 1858 and later married Margaret Barrett on July 16, 1864. (See: https://braidwoodguy.com/2022/08/09/granny-why-did-you-get-on-the-boat/ , the story of Margaret Barrett.)

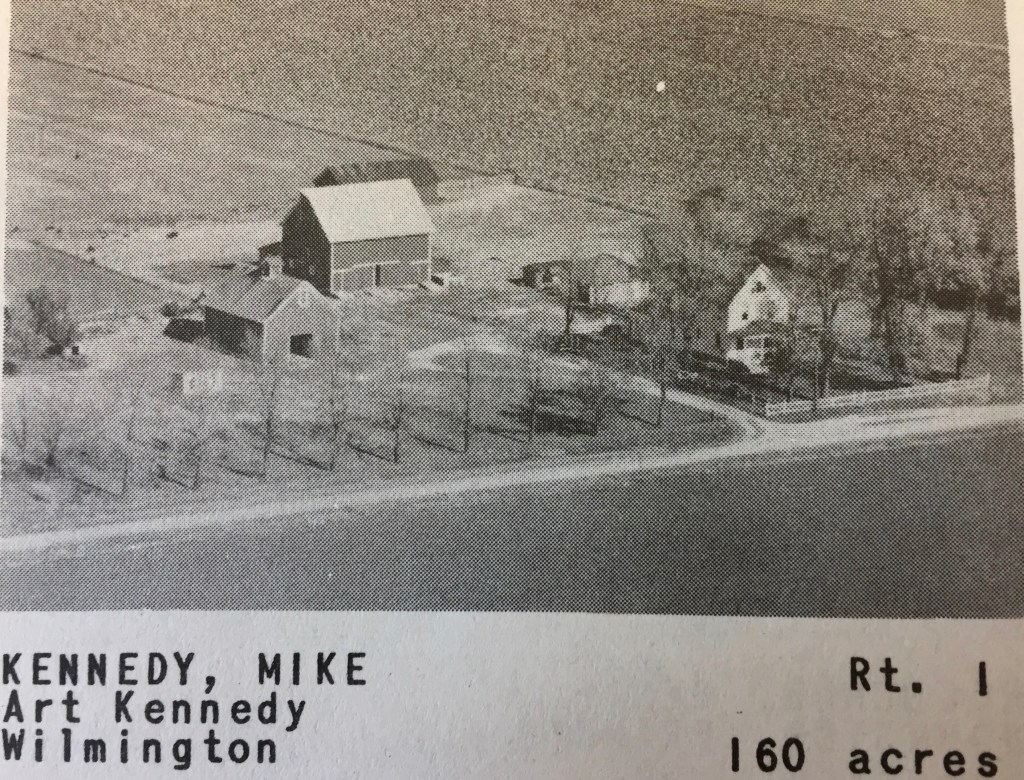

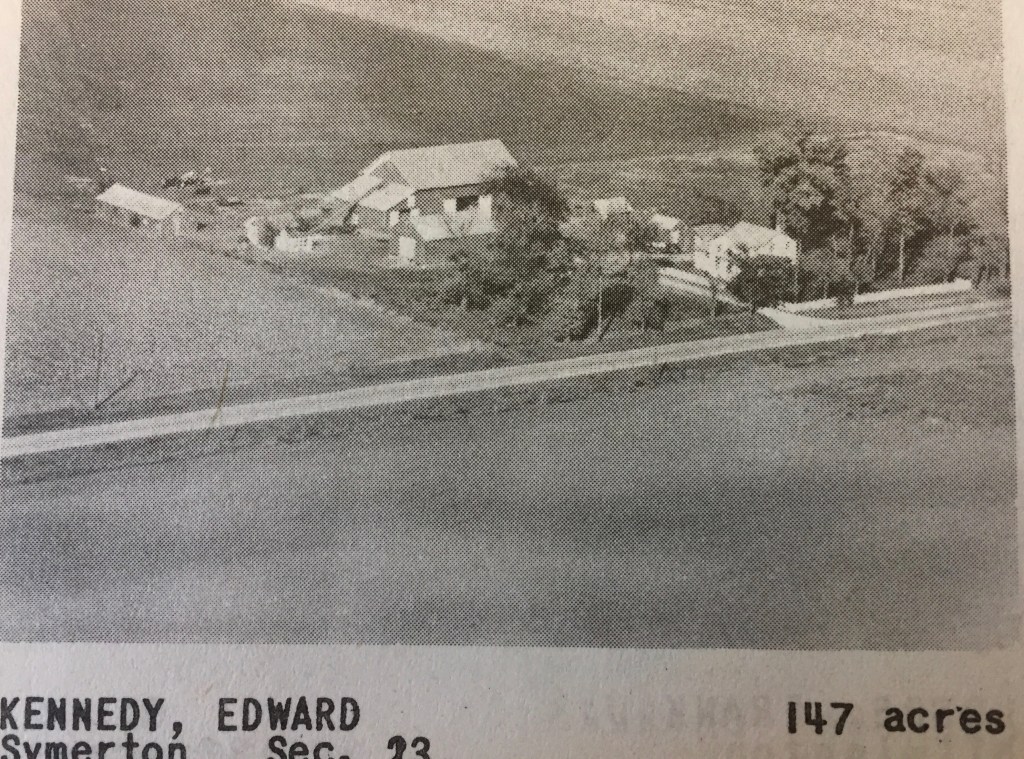

The couple had 16 children, 10 of whom survived. James Jr. (Ella McGovern); Thomas (Julia Long); Margaret (William Barry); Michael (Margaret O’Connor); William (Margaret Barry); Daniel (Margaret Klaver); Mary (Thomas Stanton); Andrew (Mary Barry); John; and Francis.

Jim’s brothers – Tom and John – also married local women. Tom married Margaret Haley and John married Catherine Shea. The patriarch of the family, John Kennedy, died on Thanksgiving Day of 1890 at the age of 90. His wife, Catherine, died in 1863 at the age of 65.

My great grandfather, James Kennedy, died on March 22, 1919, at the age of 83.

Luck and Determination

According to the Will County History (1907?), James Kennedy did make significant contributions in the Wilmington area. The “Ballingarry Boy” made the most of the opportunities available in this country.

“James Kennedy is the owner of valuable farming property in Florence Township…and is well known as one of the most prominent stock-raisers, breeders and shippers. In 1883 he built a fine residence and has made all modern improvements on his property. (He) has served as school director for eighteen years and the cause of education finds in him a warm and stalwart friend. He and his wife first attended church at the home of Roger Waters, for there was no church building at that time but later they became communicants of St. Rosa’s Roman Catholic Church at Wilmington, with which they are still identified.”

Will County History (1907?

*Special thanks to the late Oliver McMahon of Killenaule, Tipperary for researching Ballingarry history and providing a copy of “The Famine in Slieveardagh.” And thanks to the late Loretta Kennedy Tulley (Wilmington) and Patrick Leamy (Cashel, Ireland) for history materials and inspiration.

Additional Information

Wonderfully done!!!!

LikeLike