“Prejudices, it is well known, are most difficult to eradicate from the heart whose soil has never been loosened or fertilized by education: they grow there, firm as weeds among stones.”

Charlotte Brontë

Coal Mines, Strike, and African Americans

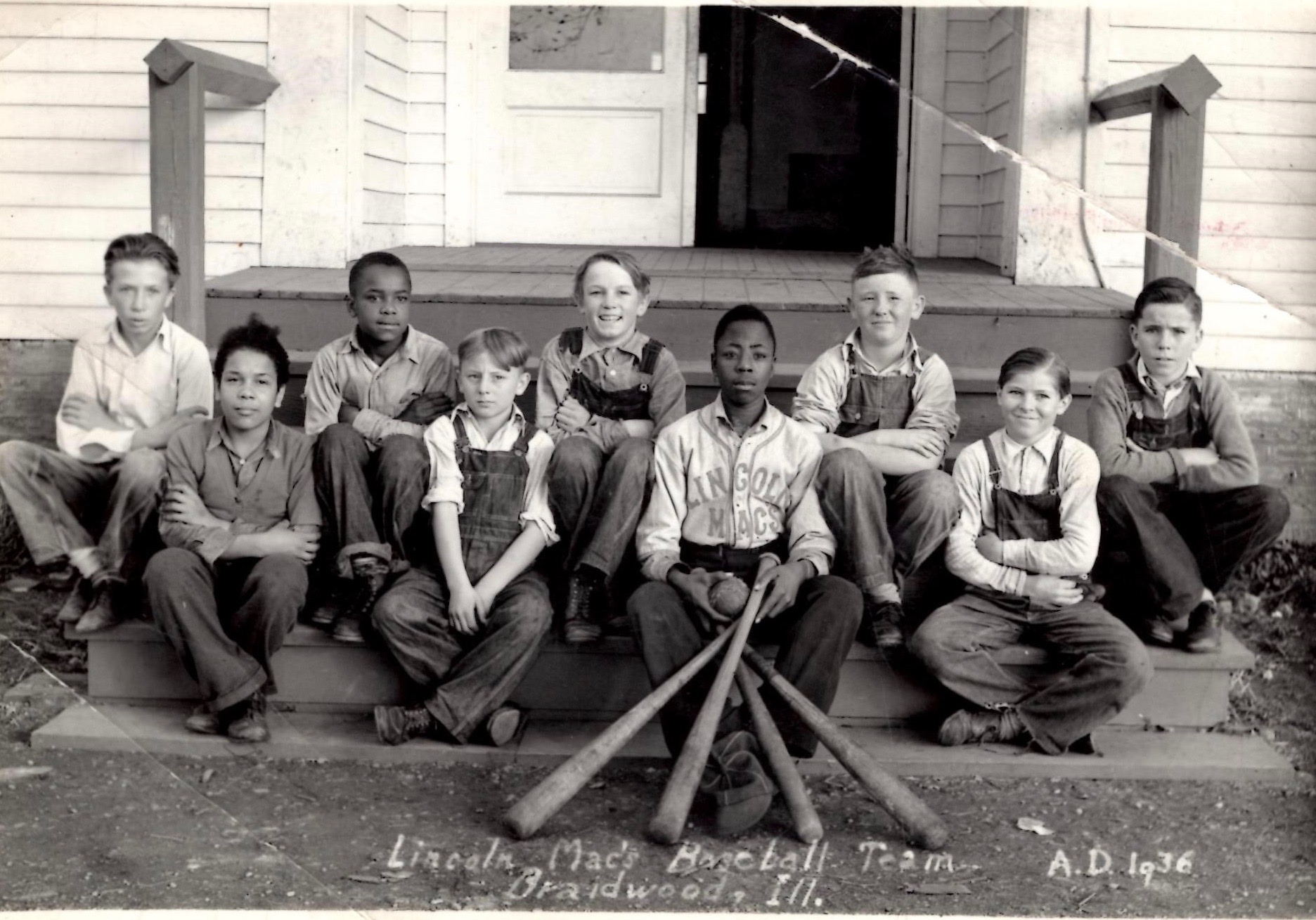

As I learned later, growing up in Braidwood was much different from the way other kids grew up. Our town of 1200 people had a history of farming, coal mining, and various ethnic groups like many other small towns. But it was different for a small town to have white and black residents who were friends and neighbors, unlike large cities where skin color kept people separate.

It turns out that Braidwood had a Black population pretty much by accident. The discovery of coal led to an industry that grew so strong by the 1880’s there was a population of approximately 5,000. The mining industry attracted immigrants from Bohemia, Scotland, and England in addition to other European countries. These immigrants brought with them their cultures and sports, including soccer. At one time, Braidwood even had a famous soccer team.

Abuses in the mining industry, such as the employment of kids in shaft mines, low wages, etc., led to a union movement in the 1870’s and 1880’s. Future mine union leader John Mitchell was one of youngsters in the Braidwood mines. A strike in 1877 by mine workers shut down several mines and caused mine owners to recruit Black strike breakers from West Virginia, Indiana, and Kentucky. Of course, these new recruits were unaware that they were being recruited to serve as replacements. That is, they were unaware until they stepped off the train in Braidwood.

Although many of the Black miners would ultimately leave the town, especially after the strike ended, some stayed and lived in various sections of Braidwood, but predominately in “lower” Braidwood. Lower Braidwood had a Black church, barbershop, and stores. Families that were in Braidwood when I was growing up included families like the Pinnicks, Turners, Carters, Dillards, and Andersons. (I knew almost everyone in town because of my paper routes.)

Buddy and Richard

Buddy Pinnick and Danny Turner were two of my baseball friends who frequented the field on Walker Street next to my house. Also included were Barney and Mike Faletti, Ronnie Foreman, Pete Cinotto, and Bobby Poppleton. The baseball gang would play for hours using the ordinary baseball sandlot rules. You know, right field out and pitcher’s hands out. Teams were selected by the captains getting first choice of players by alternate hands on the bat. If you could get two fingers on the end of the bat, you win unless the chicken claws rule was in effect. However, if the chicken claw’s rule was called, the other captain had the opportunity to kick the bat out of chicken’s claw’s hands.

Arguments, and the settlement of such, were part of the games. They usually involved tag plays, or did the runner beat the throw to the pitcher, or did the catcher (who was usually a player from the batting team) really try to make a play?

One argument ensued between Buddy and Richard over some issue. They lived within a block of one another and had been friends for some time, but this time Richard made the ultimate mistake of calling Buddy a “Nigger.” A fight broke out between them, while the rest of us cheered Buddy on. Buddy had a great personality, so it was easy for us bystanders to encourage Buddy who was one or two years older. No blows were struck, but Buddy got Richard down and held him until he said he was sorry for calling him names. Everyone in the group knew that Richard was wrong, including Richard.

It was my first lesson in prejudice.

My second lesson revolved around Buddy’s father, Bill Pinnick, who was also called “Mud.” He was always considered a gentleman and a “gentle man.” Quiet and unassuming, he would hang out at McElroy’s gas station and drink coffee with the old timers: Kenny Knorr, Sonny Boy McElroy (co-owners of the gas station), Bodie Kalugia, old man Kozlowski, my father, and others. Everyone referred to Bill as “Mud,” but now I wonder if he liked that name or not.

When the Braidwood Recreation Club was created out of the strip mine spoils in the 1950’s, the organization determined that its by-laws be classified as a private club. Braidwood residents were awarded first choice, or priority, for membership. By living in Braidwood, a person automatically had the right to join the Club for an annual fee and a one-time membership assessment. However, the Club either explicitly or implicitly denied the acceptance of Blacks into its membership, even if they lived in Braidwood. Since that time, I have been told that skin color is no longer a criterion for membership.

In addition to drinking coffee at the gas station, Mud was also a member of the volunteer Braidwood fire department. I often wondered how he felt when the fire department was called into the BRC to resuscitate or drag for a drowning victim. Mud could enter through those gates in a tragic situation as a helper but couldn’t swim there with his family. Perhaps he would have selected not to join, if he could have, not to cause any trouble. Never one to embarrass anyone, he was that kind of guy.

Ethnic Prejudice

Nationalities were often the target of prejudice labels and stereotypes. I am sure that these limitations influenced my childhood and I was no exception to this type of thinking in Braidwood. As in most cases in the 1940’s, all of us were provided with enough prejudices to last a lifetime. As I grew older, I came to learn that that these prejudices, or pre-judgments, were not really valid.

Irish were drunks, Germans were Nazis, Dutch were hard heads, English were pope haters, Bohemians were clannish, and Italians were Wops. Mexicans were lazy, Polish were stupid Polocks, and Blacks were dumb.

Wrong, wrong, wrong on every account. Was my family in Braidwood the only people who held these views? I think not. “S…” was a whore; “D…” and her son were stupid; “A… and “J…” were retarded; and suspected homosexuals were labeled. Where were kindness and respect?

Interestingly, it wasn’t the obvious Black prejudice that was most predominant in my family. That isn’t to say that my dad said things privately that I soon discovered were highly inappropriate and wrong. There were two other biases: against Bohemians and Syrians as well as and a certain group of people in Wilmington called derogatorily “yellow hammers.”

Both the Bohemians and the Syrians came from backgrounds rich in history and culture. They were hard-working, motivated people who contributed greatly to the city. Some were fine athletes in soccer and baseball.

Ignorant Labels

The other group were the “hammers.” Unfairly accused of inbreeding and incest, this group lived mostly south of the city of Wilmington on the outskirt and in Brodie’s woods. My parents thought them dirty. If we were in the same movie theater, either the Wilton or the Mar, we would literally get up and move. Folk lore has it that several families from Alabama migrated to an area just south and west of Wilmington city limits in order to find jobs at the papermill. The name “yellowhammer” may have found its roots in the Alabama State Board bird, the yellow hammer, or perhaps, because some papermills were owned by Hammermill, Inc. Or it may have been the yellow hue of workers leaving the mill with all of the dust and dirt.

Aside from dad privately referring to black people as “niggers,” he generally thought well of and respected the black families in Braidwood. The dark rocks or boulders in the farm fields were routinely called “nigger” heads, a term that is so repulsive to me that I have different difficulty writing, much less saying it. Mom would never say such words and had the highest regard especially for Mrs. and Bill “Mud” Pinnick.

I never thought of my family, especially mom and dad, as being prejudiced people. But in fact, mom and dad (especially mom) had deep-seated negative opinions about anyone who wasn’t of Irish, German, Dutch, or English origin. Fortunately, they kept their feelings and prejudices to themselves and never, to my knowledge, acted out in any way. Both mom and dad were careful about offending anyone.

Mom was German through and through. There were times when she even defended Adolf Hitler, although I’m sure she wasn’t aware for a long time of the Holocaust. Had she been aware of Hitler as the complete evil that he was, she may still have then a little defensive just because my dad was always touting the merits of the Irish in contrast to the Germans.

On the other hand, dad was Irish and Dutch. Grandma Kennedy’s mother was Dutch with the same last name as her mother’s maiden name, Klaver. It is apparent that great-grandmother Klover had this daughter, Margaret, out of wedlock, with the father totally unknown to me in the Kennedy history. This situation was almost never talked about, again there being a prejudice against unwed mothers.

As I moved out in the world, away from my house, it became increasingly apparent that the prejudices that my mom and dad had were ignorant and unfounded. I don’t necessarily blame them but wish that they had the cultural, educational, and social opportunities that I had. In fact, they saw to it that I did have those opportunities. I am so fortunate to have had these wonderful parents who were products of their generation.

Other Personal Accounts of Prejudice and Racism

Being on the Lewis College basketball team afforded me wonderful opportunities to travel and become close friends with some of my teammates while playing for the greatest coach one could ever have – Gordie Gillespie.

It also enabled me to witness first-hand the kind of racial, or nationalist, prejudice that was part of American society in the later ‘50’s and throughout the ‘60’s.

The most vivid and lasting memories of unadulterated bias happened because of my friendship with teammate, Bob Thayer. Bob is an African-American who also was a roommate of mine in college. Although we seldom talked about race issues during the three years that we were teammates, we were sensitive about these matters. As the years went on after college, we have had some very good discussions on “racism.”

On a road trip via train to Memphis in 1961, Bob was forced to move to a “colored” car once we crossed the Mason-Dixon line. I never even saw it happen, but he told me in later years about the incident. I did observe first-hand our departure off the train when Bob had to take a “colored” cab unlike the rest of us. He also had to stay at a different hotel.

That scene hit me like a ton of bricks. My good friend was carted off because of his darker skin color. I didn’t see it coming. In later years, I asked Bob about this incident. He told me that Coach Gillespie had told him what to expect on this trip and that he didn’t have to go if he thought it better. Bob asked his mother about the trip, and she told him that it might be good for him. I am sure that the trip bothered him even more than it affected me.

Bob couldn’t go to the same Joliet taverns with me even though he was 21 and I was yet underage and always was served when I was by myself. We finally settled on a bar on Patterson Road, “McGill’s,” where blacks and whites would be served and be sociable.

My white teammates didn’t seem to react to these incidents as much as I did. After all, most of them were city kids who were raised in the reality of separate facilities and neighborhoods, unlike my background of being raised in Braidwood. In our town, we knew people as people, neighbors and friends. We knew one another much more intimately because a small town is just that way. We couldn’t avoid one another even if we wanted to. Because of this, we were fairly private about our prejudices, most of which were fairly mild compared to large cities.

Lesson Learned

Lesson learned. Now, what do I do about these injustices? My responses are spelled out in some of my writings.

Front row- John T. Wells, Ray Tryne, Bill Lewis, Ray Blecha

Enjoyed the blog. FYI William “Mud” Pinnick later became the President of the Braidwood Fire Department. He was grand marshal of one or some of the parades too.

LikeLike

Mud deserved the honors of being the President and Grand Marshall. He was such a good guy.

LikeLike

Thanks to Braidwood Area History Museum President, George Kopek, we have the names of this on the picture: Back row- Jack Garret, Richard Pinnick,George Tikner, Joe Kasher, Ed Sullivan

Front row- John T. Wells, Ray Tryne, Bill Lewis, Ray Blecha

LikeLike