“The College holds, as a basic principle for its existence, the civilization of the mind, the development of the rational process by which men can work for their betterment. Any tactic which impairs the freedom of thought and expression and of due process in controversy is incompatible with the very natures of the College and will, if long allowed, work for its destruction.” Br. Paul French, President. (October 13, 1969)

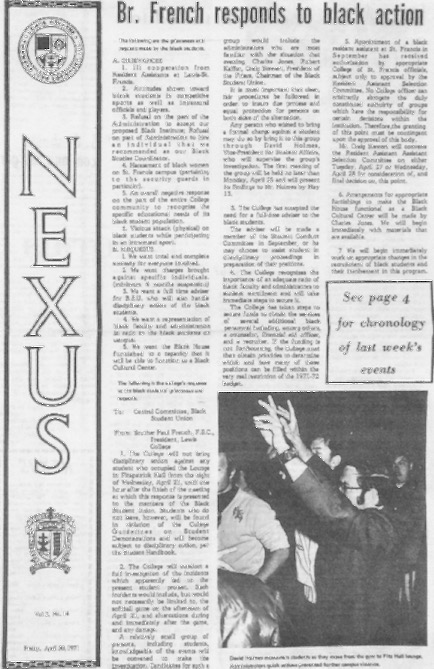

“Lounge Takeover by Blacks Provoke Hostile Reactions” Joliet Herald-News, April 24, 1971

The late 1960s and early 1970s in our country could be branded as awakened, disenchanted, and combustible. We woke up from our Camelot sleep with Viet Nam, political assassinations, and racial disparities at our doorstep. We became embroiled in the morass of riots and anger. And, we were being constantly deceived by our leaders.

The good news? As a microcosm of the greater American society, the Lewis campus confronted racial conflict, or “extreme tribalism,” with no fatalities. We came close, but we escaped bruised and unbroken.

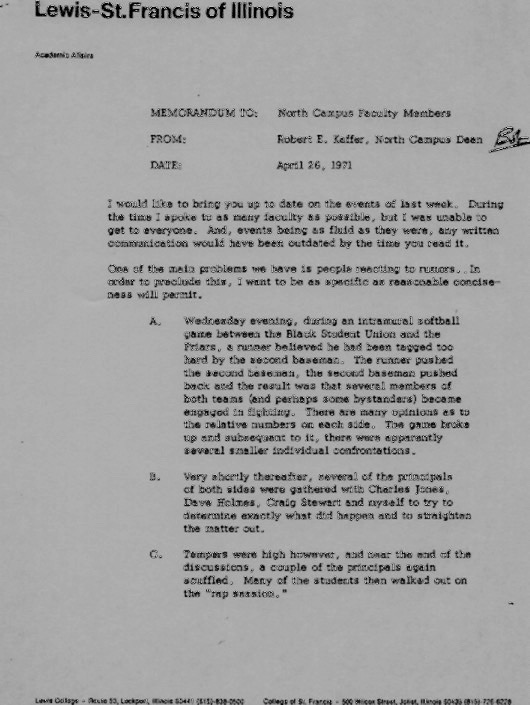

At the age of 30, I was in my fourth year as the Lewis assistant baseball coach and co-director of intramural sports with Paul Ruddy. At this time in Lewis’ history, a merger between the two neighboring Catholic colleges was in process, and we were known as Lewis-St. Francis of Illinois. The “north campus” was at Lewis and the “south campus” was at the College of St. Francis.

National racial strife had been increasing rapidly in the years preceding 1971 and it was only a matter of time when a serious physical altercation might occur on the campus. All the ingredients were there with a match being lit at an intramural softball game in the late afternoon of Wednesday, April 21st. That match, shared by a white fraternity and the Black Student Union, needed only to be struck on the rough surface around 2nd base.

Below are the dates and a few journal comments on that week in April.

Monday, April 19, 1971

Classes resumed today and we had a day off from baseball. Our baseball team just returned from a long trip to the south during spring break, where we played for 16 consecutive days including two doubleheaders. Our schedule had included colleges and universities in Florida, Georgia, and Kentucky.

The schedule continues with 7 games scheduled over the next 7 days. In the meantime, intramurals restart with badminton on Tuesday and softball on Wednesday.

Tuesday, April 20, 1971

The baseball team plays today at home against I.I.T. Game time is 3:00 p.m.

Wednesday, April 21, 1971

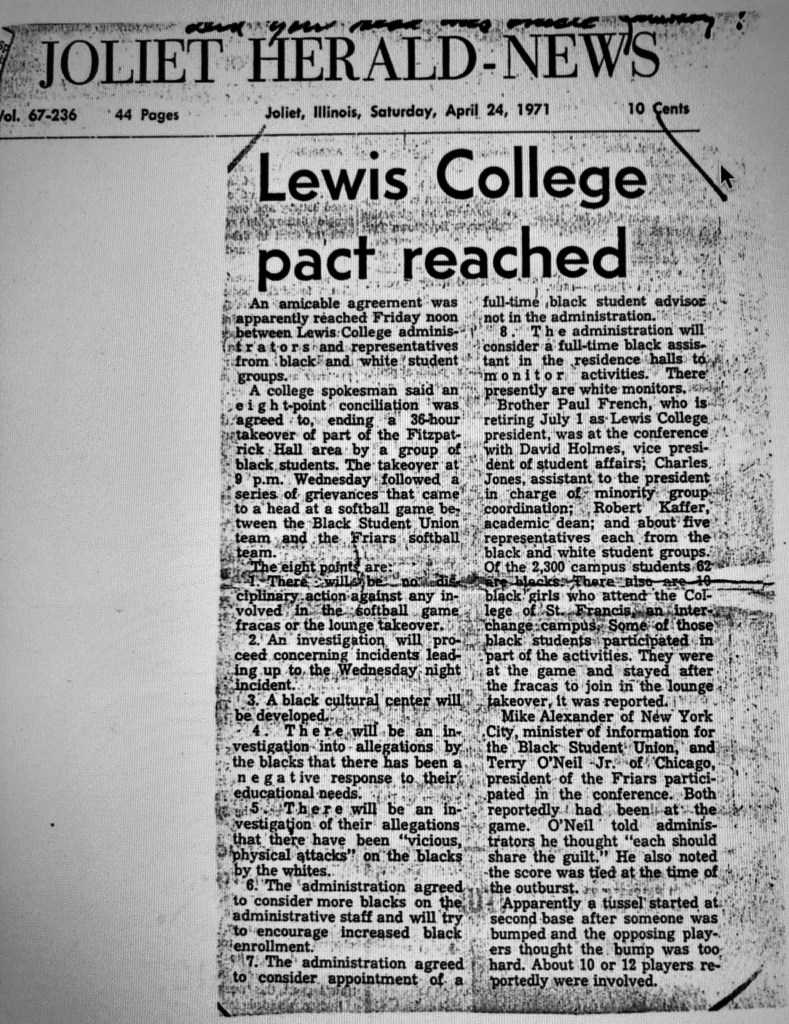

After baseball practice, I learn from Paul Ruddy that there had been a fight during a softball game between Friars and BSU. A hard tag at second base caused a shoving match between the players and the game was stopped at that point. The game was over, but the anger was not.

Comment

There had been a series of racial incidents during the year, but none resulted in anything beyond words and shoving. Given the state of national affairs, along with insults and name calling on the campus, tensions had remained high and volatile. Paul and I had been on high alert during the football and basketball games where rough contact was not uncommon.

Out of 2,300 total student population (about 1,000 on campus), there are 62 Black students who had formed the Black Student Union. All student organization members were either all white or all black.

Many Black students were increasingly frustrated since coming to Lewis. Their collective view was that the Lewis administration was not addressing their concerns, and this latest incident was the tipping point. In the evening following the softball game, they expressed their frustration by a “sit in” or a “takeover” of the Fitzpatrick Hall lounge area. That area also included the College switchboard. There they would stay until an agreement was made with the Lewis administration.

Thursday, April 22, 1971

The baseball team played a game at I.I.T in Chicago and we returned to the campus. At 6:00 p.m., a large group of white students gathered in The Catacombs snack bar where the Lewis president, Br. Paul French, attempted to explain the development and present racial situation.

I entered the facility to see if there was anything that I could possibly do to defuse the situation. At this point, there was nothing I could do. The crowd would not listen to the President, the crowd now numbering between 100-200, decided to “take this into their own hands.”

Several key administrators tried to shift the crowd out of the Catacombs into the light and steer them to the gym. I rushed over to help set up the sound system and get the students into the bleachers where we could make an appeal to temper their feelings. I estimate the crowd now at 200-300.

After attempting to get the PA to function (it didn’t), I made a verbal appeal from the floor to reconsider the wisdom of an actual Black-White physical confrontation. The crowd, several of whom were inebriated, refused to listen and were determined to “take back the lounge area” with force.

When I felt the mood of the white students shift to take action, my instinct was to sprint over to Fitzpatrick Hall, warn the Black students inside that the mob was coming to storm the place. I knocked on the door and said, “They are coming over, but they will have to go through me.” I stand in front of the entrance to block the door. I was pretty sure that there were guns inside and the approaching crowd had a few people with baseball bats.

In the meantime, a white student leader from Phi Kappa Theta had quickly followed me to the entrance. He knocked and was allowed to enter the lounge and tried to calm the black students. As expected, his reception was less than cordial.

Comment

I am not particularly brave or courageous. At 6’5” and 165 pounds, a strong breeze might have knocked me over. I did, however, have confidence that I was well-acquainted with, and friends of, both black and white students. People told me that I was fair and honest, and I really cared for all students. I just thought that I could stop any impending violence from happening. I later found out that indeed about a dozen non-students from Joliet were inside and armed. “The BSU leaders talked them out of storming out of the building to confront the crowd.” They told them not to interfere because this was “our fight.” (Direct quotes from one BSU leader.) Not everyone agreed, but the aggression was temporarily curtailed. The Lewis students were not armed.

Concurrently, a few white student leaders prevailed and helped deflect the crowd from becoming a mindless mob. Again, there were some students who would rather fight it out and take back the lounge immediately instead of processing the situation through dialogue and discussion via the Lewis administration. In any event, the mob stopped before coming to Fitzpatrick Hall.

Unlike many of the white students, my background was in Braidwood, a coal mining town where people with European and African nationalities lived and were respected as neighbors. Playing basketball and having friendships with Black teammates and roommates also aided in my understanding of those who didn’t necessarily look or act like me. Although I had deep conversations with both black and white students, my present situation reminded me of being between a dog and a fire hydrant. Only much more serious.

The physical confrontation was avoided. I believe that cooler heads prevailed among some of the more sober acting and thinking students who understood that someone could be killed. Or maybe it was some faculty members or administrators who got the mob to stop.

With the threat of physical confrontation apparently over and with police on the campus, I finally was confident that the situation was much calmer and peaceful. Anger and hate would continue for the rest of the semester, but dialogue ensued among faculty, administrators, and students. The talk sessions and negotiations very gradually defused the fiery climate and we survived. I could now go home to my wife and 5 kids, safe but exhausted.

Friday, April 23, 1971

Our baseball team traveled to Evanston where we beat Northwestern University twice. It brought back memories of infielder Mike Tynski having a career day by getting 8 hits in 1969.

I heard that an agreement had been reached between the Lewis administration and the white and black students. The black students have vacated the Fitzpatrick Hall lounge area.

Concluding Remarks

My participation during that particular evening was minimal compared to the work that was done by some extraordinary Lewis administrators and student leaders. The President, Brother Paul French, along with the vice presidents and deans, tried to reason with all constituents in a fair manner. Being reasonable, however, is a severe challenge during times of “extreme tribalism.” Brother Paul was scheduled to retire in June and his successor, Lester Carr, would be taking over. In fact, I remember Dr. Carr being quietly present in the Catacombs that night.

Key administrators included: Craig Stewart, Director of Residence; David Holmes, VP for Student Affairs; Bob Kaffer, Academic Dean; Charles Jones, Assistant to the President; and, Charles Kennedy, Professor at Lewis and JJC.

There also were some key student leaders, both black and white, who attempted to resolve critical issues. When I recently asked them about their involvement, they graciously responded with some written notes but asked that I not identify them. Their stories were pretty consistent with the documents I retrieved from the Lewis University archives.

My hope is that everyone who was involved at Lewis during these troubled times were able to grow from the experience. I know that I did.

In retrospect, that evening of April 22nd was the defining moment of who I was and who I was to be. I was neither Black nor White, on the one hand. But I was Black and White on the other hand. My role as a coach of highly skilled baseball players was coupled with my other role as co-director of intramural sports where the the athletes could have medium to low skills. I would glory in Mike Tynski’s 8 hits and thrilled to see “Cocky” Fitz score the one basket in his entire life during an intramural game. Living in ambiguity evidently was part of my makeup.

Working across cultures and nationalities would continue into the future affording me the chance to develop joint projects with Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines and Ana G Mendez University in Puerto Rico. Along with my Regis University colleagues, we developed partnerships and new ventures with private colleges across the country to help them develop non-traditional programs aimed at providing degree options for adult learners in a world steeped in hide-bound traditions.

Breaking down artificial barriers between nationalities (tribes) and man-made, false access limitations (higher education) were merely an extension of my passion for egalitarianism in the world. Looking back, this passion may have been ignited at the Fitzpatrick Hall Lounge door.

“The College will not bring disciplinary action against any student who occupied the Lounge in Fitzpatrick Hall from the night of Wednesday, April 21…”

Brother Paul French, President. (April 23, 1971)

Great article. May I suggest, though, proofreading? I hope you don’t mind that I shared. I loved the opening words of Br. French. -Tony Delgado’s sister.

LikeLike

Such interesting stories and your writing skills are great!

LikeLike

“Avoiding a Riot at Lewis 1971,” was an interesting story about a hostile time. Louis College’s staff and students addressed racial issues of that decade and were able to prevent what could’ve been a disaster.

LikeLike